RoboDIMM —The ING’s New Seeing

Monitor

Neil O’Mahony (ING)

A

brand new dome stands near the William Herschel Telescope, its white surface

reflecting the strong mountain sunshine. Inside is ING’s automatic seeing

monitor, RoboDIMM, which became operational in August last year. What was

announced as a project in the

March 2001

ING Newsletter, 4, 27, in an article by Thomas Augusteijn,

is now a fully functioning reality.

The Differential Image Motion Monitor, proposed by Sarazin and Roddier (

1990,

A&A, 227, 294) and based on a small telescope and relatively

inexpensive equipment, has over the last 10 years become the most common

seeing measurement method used in site testing and characterisation. Nowadays,

whether for control of image quality or to help decision making in queue

scheduling, DIMM-type seeing monitors have become an indispensable tool in

observatories around the world. The seeing has become just one more “meteorological”

datum that ground-based astronomy is expected to have at its fingertips.

This is why, in common with observatories in Chile and elsewhere, the ING

chose to replace its DIMM (1994–1999) with a new “robotic” DIMM. ING’s RoboDIMM

now fulfills its projected function, which was to make reliable seeing measurements

available throughout the night, requiring user intervention only for startup

and shutdown, and controlled remotely from the WHT control room.

RoboDIMM started observing in August 2002, to coincide with the first NAOMI

“science run” at the WHT. It sampled the seeing on 85 nights until December,

missing only 20% of nights, mostly due to poor weather. Around this time,

a fault with a telescope drive motor began causing significant down-time.

Now the motor has been replaced and RoboDIMM again accompanied the NAOMI

run of April 2003. It has continued in its routine job of seeing monitoring

throughout last summer without pause.

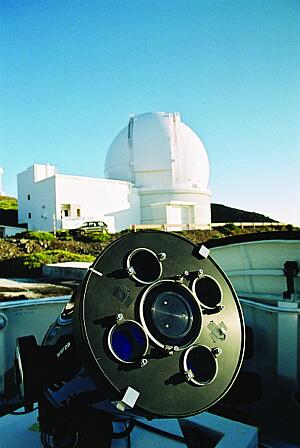

Installed atop a 5m tall tower (see

Figure 1), which

it inherited from the previous DIMM installation, RoboDIMM is built out of

a combination of off-the-shelf hardware items, with the vital addition of

custom-made software.

|

|

Figure 1 (left). RoboDIMM stands ready

at sunset for a night’s observation at the Roque de Los Muchachos observatory.

The dome is opened remotely from the WHT control room and the automatic observing

program is started. The tower, 5m tall, is located about 75m north of the

dome of the William Herschel Telescope, on a gentle slope facing unobstructedly

the prevailing winds. [ JPEG | TIFF ]

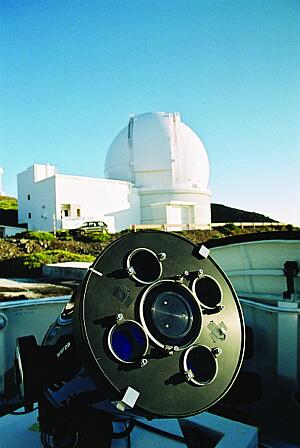

Figure 2 (right). The RoboDIMM telescope at polar park position,

with the WHT in the background. The entrance aperture forms 4 separate images

of the same star (the large central aperture is no longer used). The sub-apertures,

covered by optical wedges, are aligned along N/S and E/W (despite what the

perspective here may suggest). Both photos by R. Gorter of Startel.

[ JPEG | TIFF ]

|

The main commercially available components are a Meade12" Schmidt-Cassegrain

telescope (LX200 model), an ST-5C CCD from Santa Barbara Instruments (SBIG),

and a 12' diameter (3.7 metre) dome with motorised opening supplied by Astrohaven

in Canada. The other vital component, a mask that goes over the telescope

entrance aperture, was machined in-house, to which some specially ordered

small-deviation prisms (‘optical wedges’) were added.

It is worth mentioning some special properties of the tower, designed by

Dario Mancini of Capodimonte Observatory and used elsewhere at ORM and at

ESO’s Paranal Observatory. It consists of a vibration-proof central truss,

5.2m tall, upon which the telescope is mounted, and a second tower that surrounds

it and supports an “access platform”. In the case of RoboDIMM the latter

has been slightly widened to house the dome. The two structures are mechanically

independent, so that the telescope is isolated from vibration caused by wind

buffeting of the dome. When fully open, the dome presents a 1.5m-high barrier

to the wind, from which the telescope stands proud. Since ground layer heating

is significantly reduced at the height of the tower, we assume that the dome

induces minimal optical turbulence and has insignificant effect on the DIMM

measurements. The support struts allow the wind to flow around them, and

louvered ports in the dome floor open automatically, improving vertical airflow.

The control software was written for ING by Startel Ltd., in the Netherlands

(

http://www.startel.nl (Dutch language),

http://www.robodimm.com (in construction)).

It is a C++ program, running on a Linux-based PC, and controls all relevant

automatic functions: from choosing suitable targets and acquiring them, to

controlling the CCD, processing measurements and writing them to a database.

The telescope is commanded through a serial port connection to the PC, exploiting

a feature of the Meade LX200. The program runs a continuous sequence of tasks

but also allows user intervention and control of status and data quality

through a graphical interface.

Operation

At present the dome must be opened and closed by ING personnel, formally

the WHT Telescope Operator, from the control room of the WHT. This may be

automated in the future, and the upgrade to the telemetry system that this

would require is being considered. We may then be able to implement automatic

closure in response to adverse weather conditions.

The control program can be left running permanently, because it automatically

stops observing at sunrise and will automatically start again around the

following sunset, depending on the brightness of available targets. This

lightens the workload on the TO at the beginning of the night and helps to

provide an early seeing estimate, sometimes even before the sun has gone

down! Such an early estimate has clear applications in queue observing. If

a seeing measurement is available over the previous 5 minutes, it is published

on the ING Weather Station Web page, (

http://www.ing.iac.es/ds/weather/).

A graph of the night’s data is also publicly available (at night time) through

the Weather Page, as is the full set of archived data (or see

http://www.ing.iac.es/ds/robodimm/).

The chosen target is the brightest available star within 30 degrees of the

zenith, in a magnitude range of 2 to 4, although brighter stars can be used

in cloudy conditions. The acquisition field is almost 4×3 arc minutes,

but if no star is found in the first CCD image taken at the target position,

the program starts a search spiral. In clear conditions this usually results

in a successful acquisition within a few minutes. Once the star is near enough

to the centre of the CCD, the pointing offset of the telescope is updated,

the readout is windowed and a series of 200 images with 10ms exposure is

taken. After this, there is a brief pause while the standard deviation of

the images’ relative positions is measured and the FWHM is calculated from

this. The program then repeats the sampling and measurement cycle to provide

continuous monitoring, moving to a new star when the observing elevation

goes below 60 degrees.

A seeing measurement is made at irregular intervals of approximately 2.5minutes,

and most of that time is spent taking the 200 images in the sample. This

is a much longer duty cycle than the original ING DIMM, but it may be possible

to speed this up in future by customising the firmware on the CCD controller.

We estimate a further 20% of operative time for which no measurement is available

due to miscellaneous overheads, which may be improved upon. The software

is now fully functional with small improvements continually being added,

in close collaboration with the software authors, Startel.

Interpretation

RoboDIMM forms 4 images of the same star (see

Figure 2),

measuring image motion in two orthogonal directions from each of the two

pairs of images, from which it derives 4 simultaneous and independent estimates

of the seeing. When the system is correctly set up, these 4 measurements

should agree, over a reasonably sized sample. We find that relative sizes

vary from night to night and show a noticeable sensitivity to the focus position

of the Meade telescope, which has been observed to flop after a telescope

slew. At present the focus has to be adjusted by user command using an electronic

focuser mounted above the CCD, but we are investigating whether to fix the

focus mechanically or make automatic adjustments in the future.

The measurement published on the Weather Page is the average of 4 simultaneous

database entries, and users should be aware that this page is compiled using

data from up to 5 minutes prior to the posted time. Up-to-date and individual

measurements can be viewed by following the ‘Seeing’ link on the Weather

Page. The database values are automatically corrected for the observing zenith

distance (dividing by airmass to the power 3/5) and a wavelength of 550nm

and the time listed is that at the middle of the sample. The four instantaneous

values can differ by, say, 20%, but what matters is that there should be

no significant long term difference.

The general impression is that the average seeing published on the Weather

Page agrees reasonably well with seeing being obtained at the William Herschel

Telescope, including NAOMI and Richard Wilson’s “Slodar” wave front sensors

(see article on

page 19), and with that obtained

at other telescopes. It has shown sensitivity to all seeing conditions, registering

averages as low as 0.35" and (during the passing of a warm front) as high

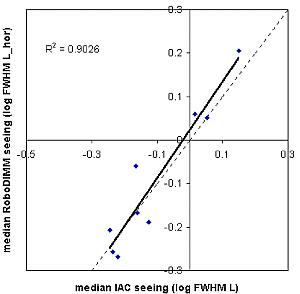

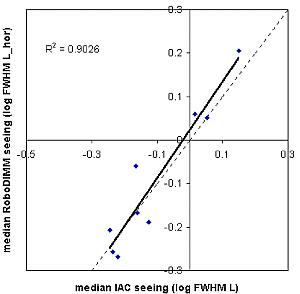

as 7"! A comparison with seeing data from the IAC DIMM (provided by the Sky

Quality Group at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias), using

simultaneous samples of several hours length from 9 nights in October 2002,

shows a 91% correlation (see

Figure 3) between the

seeing FWHM measurements made at the two instruments. The differences between

the median values is scattered around

y =

x by an amount varying

between 3 and 15% on any given night, or about 8% on average. This average

discrepancy is no larger than the internal error of either instrument. The

good agreement exists in spite of the large distance between the two monitors

(several kilometres), the factor 10 difference between their sample duty

cycles and their independent designs. Periods of rapidly fluctuating seeing

were generally excluded from the samples used in this comparison, to

avoid possible local effects.

|

Figure 3. A scatter plot of the seeing FWHM measured

by the IAC DIMM as a function of simultaneous RoboDIMM seeing. The best fit

line, close to y=x, and the large correlation coefficient (0.91) illustrate

the close dependence of these two variables. Each of the 9 points represents

the median seeing from simultaneous samples formed by a continuous period

of stable seeing lasting several hours. The logarithmic scale is necessary

to convert seeing FWHM into an approximately normally distributed variable.

[ JPEG | TIFF ]

|

While this result is encouraging and allows a good deal of confidence in

RoboDIMM’s seeing measurements, it is not conclusive, since no median below

0.6 arc seconds was used. Calibration of RoboDIMM is ongoing, including characterisation

of intrinsic errors and comparison with other seeing monitors such as NAOMI’s

Wave Front Sensor.

As regards hardware components, ING’s RoboDIMM bears a close resemblance

to the CTIO’s automatic seeing monitor (which, incidentally, is also called

RoboDIMM, but the originality of that name is disputable! See

http://www.ctio.noao.edu/telescopes/dimm/dimm.html).

There is an important difference in that the CTIO’s takes samples alternating

between 5 and 10ms exposure time. This forms two samples from which the image

motion at “zero seconds exposure” is extrapolated, following the method established

by ESO in its Chilean seeing monitors. The zero-second seeing may reportedly

be 10 – 20% larger than the 10ms estimate (

A.

Tokovinin, 2002, PASP, 114, 1156), depending on the speed

and altitude of turbulent layers. When comparing results from different sites,

it is important to bear instrumental differences in mind but we should also

remember that the strength of the exposure time “blurring” effect may differ

greatly between sites, as well as vary over time.

Conclusion

With the commissioning of the RoboDIMM seeing monitor, ING has provided its

Adaptive Optics programme with an important auxiliary instrument. It provides

a seeing FWHM estimate at regular intervals that can be relied upon to within

about 10% in stable conditions. RoboDIMM allows NAOMI performance to be monitored

in real time, and also provides essential information for AO observing in

queue mode. Additionally RoboDIMM provides all telescopes on site with data

that can help astronomers to optimally adjust telescope and instrument focus.

It allows them to make sure they are fully availing of the superb natural

seeing available at the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos.

¤

Email contact: Neil

O’Mahony (

nom@ing.iac.es)