We are taking advantage

of the wide-field near-infrared imaging capabilities of INGRID on the WHT

to construct a deep, wide area survey for Extremely Red Objects (EROs) in

archival Hubble Space Telescope Medium Deep Survey (MDS) fields.

The last five years have seen a growing appreciation of the diversity

of galaxy properties at z≥1–2. In part this has come about from an impressive

growth in our observational knowledge of galaxies at these redshifts —driven

by the availability of powerful new instruments on 4- and 8-m class telescopes.

However, an equal role has been played by the realisation of the necessity

of a multi-wavelength approach to studies of galaxy evolution at z≥1. Thus

a range of surveys spanning wavebands from the X-ray, near- and mid-infrared,

submillimeter and out to the radio, have complimented the traditional view

based on UV/optical observations. These new studies have all tended to

stress the role of dust obscuration in censuring our view of the galaxy

population at high redshifts, and especially in disguising the extent of

activity in the most active environments, both AGN and star-forming systems.

This is much more of a concern due to the very strong evolution seen in

obscured populations, which result in them dominating the bolometric emission

at high redshifts (e.g.

Haarsma

et al., 2000;

Smail

et al., 2002).

One of the most striking themes to arise from this new multi-wavelength

view of galaxy formation is the ubiquity of optically-faint, but bright

near-infrared counterparts to sources identified in many wavebands: in the

X-ray (

Cowie

et al., 2001;

Page

et al., 2001), the mid-infrared (

Pierre

et al., 2001;

Smith

et al., 2001), submillimeter (

Smail

et al., 1999;

Lutz

et al., 2001) and radio (

Richards,

1999;

Chapman

et al., 2002). This has resulted in a renaissance in interest in such

Extremely Red Objects —a class of galaxies which had previously been viewed

as a curiosity with little relevance to our understanding of galaxy formation

and evolution— comprising a mere 5–10% of the population down to K=20.

The ERO class is photometrically-defined —one frequently used definition

is I–K≥4 (or a more extreme selection of I–K≥5). This very red optical-near-infrared

colour is intended to effectively isolate two broad populations of galaxies

at z

1: those which are red by virtue of the presence of large amounts of dust

(resulting from active star formation), as well as passive systems whose

red colours arise from the dominance of old, evolved stars in their stellar

populations. The very different nature of these two sub-classes, dusty starbursts

and evolved ellipticals, has prompted efforts to disentangle their relative

proportions (

Pozzetti

& Mannucci, 2000) so that well-defined samples can be used to test

galaxy formation models (

Daddi

et al., 2000;

Smith

et al., 2002;

Firth

et al., 2002).

One particularly powerful approach is to use the morphology of the ERO

to distinguish regular, relaxed ellipticals from disturbed and dusty starbursts.

A common misconception is that the key to a successful ERO survey is

to obtain deep NIR imaging —in fact, the observationally most demanding aspect

is achieving the necessary depth in the optical to identify that a galaxy

is an ERO. For this reason, we have chosen to concentrate our survey on

fields for which deep, high-quality archival optical imaging already exists.

These fields come from the Medium Deep Survey (

Griffiths

et al., 1994) who have amassed over 500 deep HST/WFPC2 images of intermediate/

high-Galactic latitude blank fields. These represent high-resolution (0.1'')

and very deep (I~27) images of random areas of extragalactic sky. Using

a sample taken from the 100 deepest I-band MDS fields (covering an effective

area of 500 sq. arcmin) we are able to obtain morphological information

(sufficient to distinguish compact, regular evolved early-type galaxies

from the more distorted starbursts) for galaxies as faint as I=25. Six nights

of INGRID time in November 2000 and a further six in May 2001 have resulted

in over 50 MDS fields being imaged in Ks and more than 30 of these also

in J, to 5s limiting magnitudes of Ks=20 and J=22.5. It is thanks to the

generous field of view of INGRID that such a survey is possible in a reasonable

amount of telescope time. In contrast UFTI on UKIRT would take a factor

of 3–4 longer to tile each MDS field. These data will form the basis of

a sample of EROs with which we can undertake NIR spectroscopy on 8-m class

telescopes, selected from an area an order of magnitude larger than the Cimatti

et al. (2000) survey.

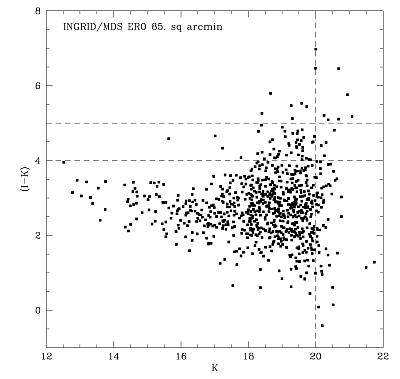

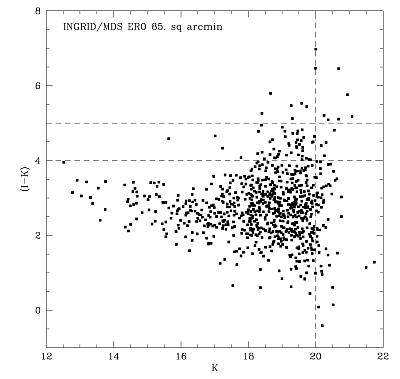

Preliminary results are shown in Figure 1. From 85 square arcmins, 55

EROs are found with I–K≥4 and 7 with I–K≥5. The samples from the full

survey of 260 sq. arcmin will be 170 and 20 respectively. A colour image

of one field made from INGRID data is illustrated in Figure 2. This survey

is supported by the Leverhulme Trust.

|

|

Figure 1. Preliminary I–K, K colour-magnitude

diagram from 85 sq. arcmins of data from our survey. These data cover 17

HST WFPC2 fields —with typical integration times of 6.0ks in the I (F814W)

passband and 3.0ks in the K-band with INGRID. The INGRID data for this survey

was taken in typically good conditions, 0.5–0.9'' FWHM, while the HST imaging

has nominally 0.1'' resolution, although poor signal to noise for the reddest

galaxies targeted here, I-K  4–5. We catalogue a total of 55 galaxies brighter than K=20 and redder

than I–K=4, of which 7 are redder than I–K=5. The equivalent sample for the

full survey will have around 170 and 20 respectively. [ JPEG | TIFF ]

4–5. We catalogue a total of 55 galaxies brighter than K=20 and redder

than I–K=4, of which 7 are redder than I–K=5. The equivalent sample for the

full survey will have around 170 and 20 respectively. [ JPEG | TIFF ]

|

Figure 2 (right). A “true colour” I/Ks image of

one of our fields. An extreme ERO, I–K>5, is visible to the south-east

of the brightest star. Other (I–K>4) EROs are indicated by arrows.The unusual

shape of the image arises from the coverage of the WFPC2 image. The field

is ~4' in diameter —meaning that the WFPC2 field is completely covered by

INGRID, irrespective of the roll angle of HST when the observations were taken.

The image reaches 5σ point source sensitivities of K~20 and I~26. [ JPEG | TIFF ]

|

References:

- Chapman, S. C., Lewis, G. F., Scott, D., Borys, C., Richards,

E., 2002, ApJ, 570, 557. [ Citation

in text | ADS

]

- Cimatti, A., Villani, D., Pozzetti, L., di Serego Alighieri, S.,

2000, MNRAS, 318, 453. [ Citation

in text | ADS

]

- Cowie, L. L., et al., 2001, ApJ, 551, L9. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Daddi, E., Cimatti, A., Renzini,A., 2000, A&A, 362,

L45. [ Citation in text | ADS

]

- Firth, A. E., et al., 2002, MNRAS, 332, 617. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Griffiths, R. E., et al., 1994, ApJ, 435, L19. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Haarsma, D. B., Partridge, R. B., Windhorst, R. A., Richards,

E. A., 2002, ApJ, 544, 641. [ Citation

in text | ApJ

]

- Lutz, D., et al., 2001, A&A, 378, 70. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Page, M. J., Mittaz, J. P. D., Carrera, F. J., 2001, MNRAS,

325, 575. [ Citation in text | ADS

]

- Pierre, M., et al., 2001, A&A, 372, L45. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Pozzetti, L., Mannucci, F., 2000, MNRAS, 317, L17. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Richards, E. A., 1999, ApJ, 513, L9. [ Citation in text | ADS

]

- Smail, I., et al., 1999, MNRAS, 308, 1061. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Smail, I., Ivison, R. J., Blain, A. W., Kneib, J.-P., 2002, MNRAS,

331, 495. [ Citation in text | ADS

]

- Smith, G. P., et al., 2001, ApJ, 562, 635. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

- Smith, G. P., Smail, I., Kneib, J.-P., Davis, C. J., Takamiya,

M., Ebling, H., Czoske, O., 2002, MNRAS, 333, L16. [

Citation in text | ADS

]

Email contact: David

Gilbank (

D.G.Gilbank@durham.ac.uk)