|

ING Scientific

Highlights

in 1997*

*Astronomical

discoveries following from observations carried out with the ING

telescopes

[ 1996

Scientific Highlights | 1998 Scientific Highlights ]

[

SOLAR

SYSTEM | STARS | GALAXIES |

OBSERVATIONAL

COSMOLOGY ]

COMET HALE-BOPP:

FIRST EVER IMAGES OF A NEUTRAL GAS TAIL

CoCAM, WHT+UES

The 1997 International Time Project

on comet Hale-Bopp was a great success and several major discoveries were

made, including the first detection of a neutral gas tail, the observation

of "cyanogen shells" and the detailed study of the rotation of the nucleus.

Members of the Comet Hale-Bopp European Team participated in this project.

This team was formed in early 1996 to co-ordinate European observing efforts

because comet Hale-Bopp provided an extraordinary opportunity for scientists

to observe a bright comet in great detail with the most advanced instrumentation,

including the last generation of digital detectors.

Observations carried out to study

the distribution of sodium atoms in comet C/1995 O1 Hale-Bopp led to the

discovery of a new type of comet tail. Sodium atoms had previously been

seen near the center of other comets, but these observations revealed for

the first time a straight tail of sodium 6 degrees long.

The discovery images were taken

with the CoCAM wide-field CCD camera, built and operated by staff at the

Isaac Newton Group, set up next to the INT. CoCAM consists of a 35-mm camera

zoom lens working at f/3.5 and imaging onto a 2220 × 1180 pixel EEV

CCD chip, whose pixel size of 22.5m square corresponds to 26",

thereby achieving on the sky a total field of 17° × 9°.

On 16 April members of the European

Comet Hale-Bopp Team made several exposures of the comet through a narrow

filter that isolates emission from sodium atoms, and to their great surprise

they found that these atoms were distributed over an enormous region in

and around the comet. Contrary to earlier observations of bright comets

near the Sun, the sodium was present not only in the region next to the

cometary nucleus, but there were also large amounts in the region of the

cometary tails.

Following a careful analysis of

the observed distribution of these atoms, the astronomers concluded that

comet Hale-Bopp displayed a third type of tail never seen before and consisting

of sodium atoms.

Whereas the well-known ion and

dust tails so prominently displayed by Hale-Bopp show a large amount of

structure, the new sodium tail had a completely different appearance. It

takes the form of a long tail approximately 600,000 km wide and 50 million

km long, in a direction close but slightly different to that of the ion

tail. While the electrically charged particles in the ion tail are accelerated

to large velocities by the solar wind (very fast atomic particles emitted

by the Sun), the sodium atoms are released from dust grains and then accelerated

in the antisolar direction by simple fluorescence. These latter conclusions

were achieved thanks to observations with the William Herschel Telescope.

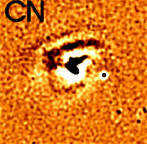

Other interesting features reported

by the European Comet Hale-Bopp Team include the spiral-jet and arc structures

observed with the Jacobus Kapteyn Telescope in the inner coma of the comet.

The astronomers made use of a CN and a blue continuum filter, obtaining

an expansion velocity for CN of 1.3 km/s.

| 1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

| 4 |

|

5 |

|

6 |

|

| 7 |

|

8 |

|

9 |

|

1.- Discovery image of the

sodium tail in Comet Hale-Bopp taken on 16 April. The tail appears as a

very straight narrow feature extending from the head of the comet to the

upper left. (a) [ Small GIF | GIF

| TIFF ] This spectrum corresponds to the sodium

tail 3.1° from the nucleus, obtained with the WHT plus the Utrecht

Echelle Spectrograph (UES) on April 23.9 UT. Sky lines due to OH and Na

are labelled. The cometary NaD lines are clearly observable due to an apparent

Doppler shift of 144 km/s from the terrestrial emission (Cremonese et al,

1997, Astrophys J, 490, L200). (b) [ GIF

| BMP ] The picture on the right is an image

of Comet Hale-Bopp showing the usual ion and dust tails of the comet, taken

a few minutes before the discovery of the sodium tail. The dust tail is

the broad tail pointing straight upwards, while the ion tail is the filamentary

structure to the left. Comparison of the two images shows how the sodium

tail has a completely different appearance to the other tails of the comet.

2.- The 28th February saw first

images of Hale-Bopp obtained at the INT Prime Focus camera. This image

was taken through an RGO-B filter. [ GIF | BMP

]

3.- Filamentary ion tail of

comet Hale-Bopp on 9 April. This is a 300 s exposure taken with CoCAM using

a narrow band filter centered at 618.5 nanometers to isolate H2O+

emission. [ GIF ]

4.- CoCAM camera. [ JPG

| BMP ]

5.- This image was taken by

the IAC Hale-Bopp Team at the Auxiliary Port of the WHT on 4 February.

A broad-band R filter was used for the observation and an exposure time

of just two seconds. A complex series of twisted and spiral jets can be

seen in the processed image, with many jets splitting into two, three,

or even more parts. [ JPG ]

6.- This Z filter image was

taken on 1 March with the WHT. Two dusty shells are visible. [ GIF

]

7.- Sum of four 10 s, three

20 s and five 5 s CoCAM exposures with no filters taken on 19 March. The

filaments visible in the dust tail are synchronic bands of material, i.e.,

ejected at the same time from the nucleus. [ GIF

]

8.- Observations obtained by

the European Comet Hale-Bopp Team with the JKT on 5 March revealed both

spiral-jet and arc structures. These images were taken through a CN (cyanogen)

and a H2O filter with Laplacian filtering applied to the reduced

images. The CN image shows a faint arc below the nucleus due to the expansion

of a shell of cyanogen-emitting dust. [ JPG ]

9.- 300 s CoCAM image of comet

Hale-Bopp taken on 13 April through a H2O+ filter

and a 3 s exposure of the inner coma using no filters (inset).

Both images show the extraordinary possibilities of the wide field imaging

device CoCAM. [ GIF ] |

References

-

G Cremonese et al, 1997, "Comet C/1995

O1 (Hale-Bopp)", IAU circular 6631.

-

G Cremonese et al, 1997, "Comet C/1995

O1 (Hale-Bopp)", IAU circular 6634.

-

G Cremonese et al, 1997, "Neutral

Sodium from Comet Hale-Bopp: A Third Type of Tail", Astrophys J,

490,

L199.

-

A Fitzsimmons, 1997, "Comet C/1995

O1 (Hale-Bopp)", IAU circular 6638.

-

D Pollacco, 1997, "Comet Hale-Bopp:

First Light on CoCAM", Spectrum Newsletter, 14, 12.

DETECTION OF

SPIRAL WAVES IN STELLAR ACCRETION DISC

INT+IDS

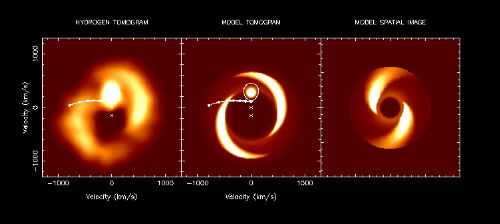

For the first time, astronomers

detected spiral structure in the disc of gas that surrounds one of the

stars in an interacting binary star system. The observed system is known

as IP Pegasi. IP Pegasi is an eclipsing dwarf nova, a subclass of cataclysmic

variables, consisting of a K5 secondary star of 0.5 solar masses losing

mass to a white dwarf of 1.0 solar masses in a 3.8-hour orbit. At semi-regular

intervals of about three months the system brightens by 2 magnitudes as

the mass transfer through the accretion disc suddenly increases.

The disc is smaller than the radius

of the Sun, so it is not possible to resolve it directly in any telescope.

The technique used involved measuring the velocity of the gas by looking

at the Doppler shift in its spectrum. As the stars revolve around each

other in their 3.8-hour orbit, the observers got successively different

views of the disc. By using a technique called "tomography", they were

able to reconstruct a picture of the flow pattern of the gas.

The results showed a two-armed

trailing spiral in the outer part of the disc. Such spirals are thought

to be created by tidal forces due to the gravitational pull of the normal

star. The formation of such spirals had been predicted, but this is the

first positive detection.

This discovery was made thanks

to observations carried out at the INT using Service time. The Service

programme at the ING telescopes is well suited for undertaking a quick

look at new cataclysmic variables or providing complementary emission-line

information on old ones. But the programme's main advantage is that it

offers the observers the opportunity of some flexibility over the predetermined

schedule to cover unexpected events such as nova outbursts. Indeed the

astronomers observed IP Pegasi while it was on the rise to outburst with

the Intermediate Dispersion Spectrograph (IDS) on the INT, which resulted

in the discovery of spiral structure in the binary's accretion disc.

|

| A

hot disk of gas surrounding a compact white dwarf star in the constellation

of Pegasus has recently been revealed to be imprinted with this dramatic

pattern. The white dwarf is part of the interacting binary star system

IP Pegasi and the disk of gas is an accretion disk formed of material lost

from a companion star and falling toward the white dwarf. The disk itself

is smaller than the Sun's diameter, so the spiral pattern can not be imaged

directly by telescopes. Instead, the spiralling disk of gas is mapped over

a series of observations using a spectroscopic technique known as Doppler

"tomography". The left panel above shows a tomogram, the directly measured

gas velocity map for the system. The relative brightness corresponds to

the intensity of light emitted by Hydrogen gas moving at the indicated

velocity. The position at the center of this panel represents the velocity

of the binary system's center of mass. In the middle panel, a simple model

velocity field consistent with the measurements is shown. At the right,

the calculated position map of the IP Pegasi accretion disk reveals a striking

two armed trailing spiral pattern [ JPG | BMP

]. |

References

-

E T Harlaftis and D Steeghs, 1997,

"Spiral Waves in a Solar-size Accretion Disc", Spectrum Newsletter,

13,

4.

-

D Steeghs et al, 1997, "Spiral structure

in the accretion disc of the binary IP Pegasi", MNRAS, 290,

L28.

THE FIRST L-TYPE

BROWN DWARF

WHT+ISIS, INT+Prime Focus

Since the discovery of the first

brown dwarf in 1995 by the WHT, it has been proved that objects with masses

between those of stars and planets can be formed in nature and several

observations of brown dwarfs have been reported.

To directly detect single brown

dwarfs of known age, distance and metallicity, the ideal place to search

is within young open clusters. Many brown dwarf surveys have been conducted

in the Pleiades open cluster. This is because the Pleiades cluster is near

enough that the lower main sequence is not beyond the limits of detection,

but far enough away that the area of sky covered is not too large. The

cluster is young enough so that any brown dwarfs will be relatively bright.

The discovery of the first brown dwarfs in a small survey of the Pleiades

suggests that a large number of very low mass objects may populate this

cluster.

With the aim of searching for

new Pleiades brown dwarfs, a deep ITP CCD I,Z survey was performed covering

1 deg2 within the central region of the

cluster. Over 50 faint (I =>17.5), very red (I–Z => 0.5) objects were detected

down to I~22. Their location in the I–Z color diagram suggested cluster

membership. According to current evolutionary models, they should have

masses in the interval 30 – 80 MJup (1 MJup ~ 10–3

solar masses).

The most secure Pleiades brown

dwarfs are those with kinematic information that supports cluster membership

and lithium detection that confirm their substellar status. After spectroscopic

observations, several candidates were confirmed as brown dwarfs, among

them, Roque 4 (45 MJup, I=19.75, M9 V) and Roque 25 (35 MJup,

I=21.17, early L), the coolest and faintest brown dwarfs ever observed.

Roque 25 is a benchmark brown dwarf in the Pleiades because it is the first

known one that belongs to the L-type class. The optical spectrum of Roque

25 is characterised by the following features: (1) the lack of strong molecular

absorption band heads in the range 640–760 nm, in particular, the strong

TiO bands starting at 705.0 nm are absent or extremely weak in Roque 25;

(2) the molecular systems of CaH, CrH, and FeH become as strong or stronger

than the systems of TiO and VO; (3) the atomic lines of KI and CsI that

are very strong in L-type objects are weaker in Roque 25.

|

| INT image of Roque 25, the

coolest (Teff ~ 2050 K) and faintest (I=21.17) brown dwarf ever observed,

and the first one belonging to the L-type class. [ GIF

] |

Roque 25 provides evidence that

the initial mass function extends down to about 0.035 solar masses and

serves as a guide for future deep searches for even less massive young

brown dwarfs.

References

-

M R Cossburn et al, 1997, "Discovery

of the lowest mass brown dwarf in the Pleiades", MNRAS, 288,

L23.

-

E L Martín et al, 1998, "The

First L-Type Brown Dwarf in the Pleiades", Astrophys J, 507,

L41.

-

D J Pinfield et al, 1997, "Brown

dwarf candidates in Praesepe", MNRAS, 287, 180.

-

M R Zapatero Osorio, R Rebolo, and

E L Martín, 1997, "Brown Dwarfs in the Pleiades cluster: a CCD-based

R, I survey", Astron Astrophys, 317, 164.

-

M R Zapatero Osorio, E L Martín,

and R Rebolo, 1997, "Brown Dwarfs in the Pleiades cluster. II. J, H and

K photometry", Astron Astrophys, 323, 105.

-

M R Zapatero Osorio et al, 1997,

"New Brown Dwarfs in the Pleiades Cluster", Astrophys J, 491, L81.

OBSERVATIONAL

EVIDENCE THAT ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES ARE PRODUCED BY FUSION

INT+Prime Focus

It has been known since the 80's

that hidden behind the apparent simplicity and uniformity of elliptical

galaxies are some unusual properties. Almost half of the ellipticals which

have been studied show faint luminous arcs which are called shells. The

nucleus of between 20 and 30% of ellipticals rotate in the opposite or

orthogonal direction from the rest of the galaxy. An undetermined number

of ellipticals have rings or polar disks with stars, gas and dust. The

existence of such structure can only be understood as a result of accretion

or fusion processes between existing galaxies and not as a result of monolithic

collapse during the formation stage. In fact the presence of two counter

posed tidal tails is unequivocal evidence for the fusion of two disk galaxies.

The fact that the tails are diluted with time until they become unobservable

has made it difficult in the past to obtain fundamental proof of the origin

of ellipticals from the fusion of spiral galaxies.

|

CCD image of the peculiar

elliptical galaxy NGC 3656 (Arp 155) obtained in the R band with the INT.

The first of the two tails emerges to the west (right) and then curves

to the north (up). The three objects in line with the end of the tail are,

from south to north, a dwarf galaxy and two stars, the northernmost of

which hides a small galaxy in its halo. It is as yet unknown if the galaxies

are physically associated with the tail. The second tail emerges from the

east side of the galaxy and extends towards the north. [ GIF

] |

This proof has been obtained as

a result of observations with the INT of the peculiar elliptical galaxy

NGC 3656. This galaxy had been understood to be the result of a minor fusion

(an elliptical galaxy swallowing a smaller galaxy) due to the presence

of photometric shells and a nucleus which rotates orthogonally. The INT

data, after being treated with a special equalising process for the detector's

photometric response, have revealed an extensive luminous halo and two

tidal tails. Such tails are incompatible with minor fusion and suggest

that a major fusion has taken place between two galaxies with disks of

similar size in direct orbit.

References

-

M Balcells, 1997, "Two tails in NGC

3656 and the major merger origin of shell and minor-axis dust lane elliptical

galaxies", Astrophys J, 486, L87.

EVIDENCE OF TWO

KINEMATICALLY DIFFERENT STELLAR SYSTEMS IN NGC 1068

WHT+ISIS 2D-FIS

NGC 1068 is a nearby (~ 22.7 Mpc),

luminous and well-studied active galaxy. Despite of being the Seyfert 2

prototype galaxy, it shows broad permitted lines in polarised light. The

current interpretation of this result is that NGC 1068 has a Seyfert 1

nucleus obscured from our direct view. The existence of a large concentration

of molecular gas and dust in the nucleus of NGC 1068 supports this hypothesis.

The kinematic off-centering between

the inner and the outer regions of NGC 1068 observed in the gas velocity

fields could indicate the presence of a non-symmetric contribution to the

gravitational potential. Both regions exhibit kinematic minor axes aligned

and could have similar systemic velocities. However, their kinematic centers

are displaced by ~ 2.5", and this can be interpreted as two kinematically

different stellar systems rotating around parallel but with shifted axes.

|

|

| The 2D-FIS system

consists of a bundle containing 125 optical fibers distributed in the focal

plane of the WHT. It can be used in combination with ISIS. Left: The circles

at position P1 represent the distribution of the fibers in the focal plane

of the WHT. The cross indicates the location of NGC 1068 optical nucleus.

Right: Spectra from the observed region of NGC 1068 in the range 8503-8748

Å (extracted from B García-Lorenzo et al, Astrophys J, 483,

L99). [ GIF1 | TIFF1

] [ GIF2 | TIFF2 ] |

The almost discontinuous transition

between the inner and outer regions rather suggests a strong decoupling

between both zones, as if they corresponded to two distinct stellar systems.

This leads to the interesting possibility of considering NGC 1068 as a

merger remnant: a satellite galaxy could have been captured by the primary

galaxy, a merged core being situated close to the disk center of the primary.

References

-

B García-Lorenzo et al, 1997,

"Evidence of two kinematically different stellar systems in NGC 1068",

Astrophys

J, 483, L99.

Rawlings et al, 1995, "A radio

galaxy at redshift 4.41", Nature, 383, 502

FIRST DETECTION

OF THE OPTICAL COUNTERPART OF A GAMMA-RAY BURST

WHT+Prime Focus, INT Prime

Focus

Since their discovery Gamma-Ray

Bursts (GRBs) have been one of astronomy's great mysteries. The distribution

and properties of the bursts are explained naturally if they lie at cosmological

distances, but there is an opposing view that they are relatively local

objects, perhaps distributed in a very large halo around our Galaxy. For

a long time it was expected that the detection of a counterpart at other

wavelengths would provide the key to understanding the GRB phenomenon.

However, such counterparts were not found, in spite of much effort during

the last 25 years. The main problem was the lack of fast and accurate GRB

positions. With the launch of the Wide Field Cameras (WFCs) on board the

Italian-Dutch X-ray satellite BeppoSAX this has changed. For the first

time GRB positions can be determined with accuracies of a few arcminutes

within a few hours after the burst, unprecedented in GRB astronomy.

Finally the situation changed

dramatically on February 28, 1997 when a team of astronomers led by Jan

van Paradijs of the University of Amsterdam and the University of Alabama

in Huntsville pointed the William Herschel Telescope to the part of the

sky where shortly before a new GRB had been detected (GRB 970228) by the

Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor onboard BeppoSAX satellite.

On February 28, UT 23 h 48 m,

20.8 hours after the GRB occurred, the astronomers obtained a V-band and

an I-band image (exposure times 300 s each) of the WFC error box with the

Prime Focus camera of the William Herschel Telescope. The 1024 ×

1024 pixel CCD frames cover a 7.2' × 7.2' field, well matched to

the size of the GRB error box. The limiting magnitudes of the images were

V=23.7, and I=21.4. They obtained a second I-band image on March 8, UT

21 h 12 m with the same instrument on the WHT (exposure time 900 s), and

a second V-band image on March 8, UT 20 h 42 m with the Isaac Newton Telescope

(exposure time 2500 s).

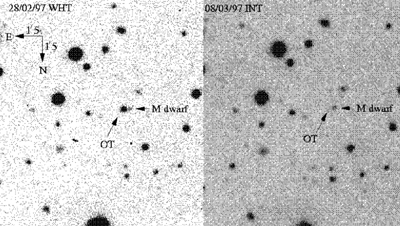

|

| Discovery image of the optical

counterpart of a Gamma-Ray Burst (GRB). OT: Optical Transient. The left

panel shows the part of the sky where the GRB occurred as seen by the William

Herschel Telescope. The right panel shows the same part of the sky only

a few days later with the Isaac Newton Telescope, when the source had already

become much fainter. After more than two decades of intensive searches

for signs in the visible light of these extremely energetic events in the

Universe, these two images show that GRBs can be spotted with optical telescopes

from the ground. This discovery is helping scientists to unreveal the true

nature of the cataclysmic events known as Gamma-Ray Bursts. [ GIF

] |

A comparison of the two image

pairs immediately revealed one object with a large brightness variation:

it was clearly detected in both the V- and I-band images taken on 28 February,

but not in the second pair of images taken on 8 March. The position of

this object was coincident with all the known error-boxes of GRB 970228.

This led the discovery team to conclude that they had identified the first

example of optical afterglow of a GRB.

Following this first detection,

other optical counterparts of GRBs have been discovered and followed up

photometrically and spectroscopically. In most of these subsequent detections

the ING telescopes have played an important role.

References

-

T Galama et al, 1997, "The decay

of optical emission from the gamma-ray burst GRB 970228", Nature,

387,

479.

-

T Galama et al, 1997, "Radio and

optical follow-up observations and improved interplanetary network position

of GRB 970111", Astrophys J, 486, L5.

-

P J Groot and T J Galama, 1997, "Optical

Afterglow of a Gamma-Ray Burst: GRB970228", Spectrum Newsletter,

14,

8.

-

P J Groot et al, 1997, "GRB 970228",

IAU

circular 6584.

- J van Paradijs et al, 1997, "Transient

optical emission from the error box of the gamma-ray burst of 28 February

1997", Nature, 386, 686.

DISCOVERY

OF THE THIRD MOST DISTANT QUASAR AND THE HIGHEST REDSHIFT RADIO AND X-RAY

SOURCE

INT+Prime Focus, WHT+ISIS

During an imaging survey of the

evolution of the space density of radio-loud quasars, a quasar at z=4.72

was discovered. This quasar, GB 1428+4217, is the third most distant quasar

and the highest redshift radio and X-ray source currently known. It has

a radio flux density at 5 GHz of 259 ± 31 mJy and an optical magnitude

of R ~ 20.9. The rest frame absolute UV magnitude is M (1450 Å) =

–26.7. Another radio-loud quasar was discovered during the same CCD imaging

survey, GB 1713+2148, with z = 4.01. Combined with earlier survey results,

these objects give a lower limit on the space density of quasars with radio

power P5 GHz > 5.8 × 1026 W Hz–1

sr–1 between z = 4 and z = 5 of 1.4 ± 0.9 × 10–10

Mpc–3.

|

| B and R image of GB1428+4217

(the very red object in the center). GB1428+4217 is the third most distant

quasar and the highest redshift radio and X-ray source currently known.

This picture was taken using the Prime Focus camera at the INT. [ GIF

] |

References

-

A C Fabian et al, 1997, "The extreme

X-ray luminosity of the z=4.72 radio-loud quasar GB 1428+4217", MNRAS,

291,

L5.

-

I M Hook and R G McMahon, 1998, "Discovery

of radio-loud quasars with z=4.72 and z=4.01", MNRAS, 294,

L7.

OTHER HIGHLIGHTS

A new slitless spectroscopy technique

was developed to simultaneously detect and measure the kinematics of planetary

nebulae in external galaxies, and first experiments with ISIS spectrograph

on the WHT proved successful. Plans now exists to build a dedicated instrument.

Construction would take place in Groningen and at ASTRON.

An international team led by astronomers

of the University of Wyoming announced the discovery of a new type of star.

In many binary systems, the initially more massive star ends its life and

becomes a white dwarf, while the initially less massive star tries to evolve

normally, but all the while loses mass to the white dwarf. Eventually,

all that remains of the less massive star is an exposed stellar core with

a size near that of the planet Jupiter and a mass of only 5/100th or so

of its original value. Having used up or lost essentially all its hydrogen,

this very small star has no remaining energy generation. It cannot ever

become one of the usual stellar end-products. Therefore, it has a structure

unlike any other kind of known star. This discovery was made thanks to

observations with the WHT.

|