|

|

THE BEST CANDIDATE TO UNDERGO A SUPERNOVA EXPLOSION

WHT+UES

The Utrecht Echelle Spectrograph (UES) on the William Herschel Telescope has allowed astronomers to monitor Rho Cassiopeiae (ρ Cas or HD 224014) in detail from 1993 to 2002. The observations were aimed at investigating the processes occurring when yellow hypergiants approach and bounce against the Yellow Evolutionary Void, and the results revealed almost regular variations of temperature within a few hundred degrees. However, what happened with ρ Cas during the summer of 2000 went beyond anybody's expectations.

The star suddenly cooled down from 7,000 to 4,000 degrees within a few months. Astronomers discovered molecular absorption bands of titanium-oxide (TiO) formed in the slowly expanding atmosphere, suggesting that they had witnessed the formation of a cool and extended shell which was detached from the star by a shock wave carrying a mass equal to 10% of our Sun or 10,000 times the mass of the Earth. This is the highest amount of ejected material astronomers have ever witnessed in a single stellar eruption.

|

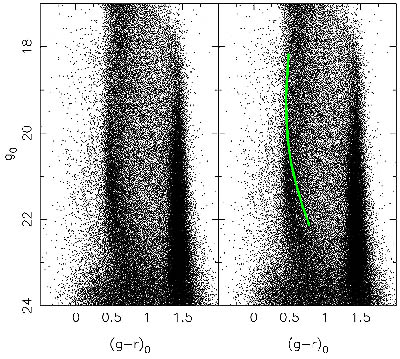

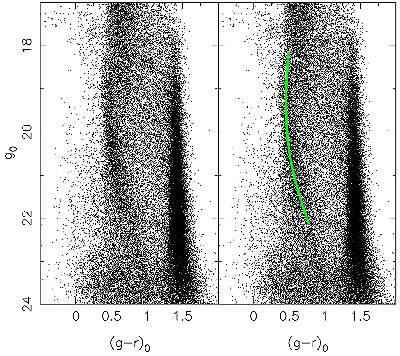

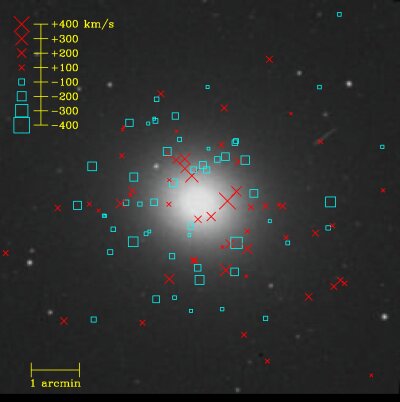

| Near-IR TiO absorption bands observed

during the outburst of ρ Cas in 2000 July (middle solid line). The

weak TiO bands around 7070 Å have distinct shapes (at vertical solid

lines), also observed in Betelgeuse (lower solid line). The synthetic spectrum

of ρ Cas is computed with only TiO lines (of the P-, Q-, and R-branches;

upper dotted line), while that of Betelgeuse (lower dotted line) also includes

molecular and atomic lines. Note that the TiO bands are considerably broader

than the telluric lines. [ GIF

] |

|

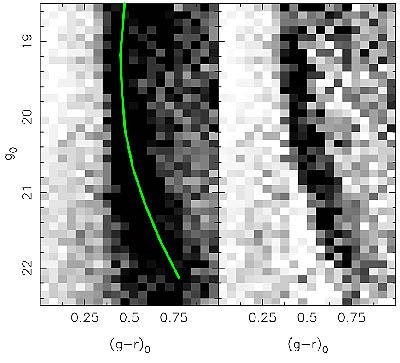

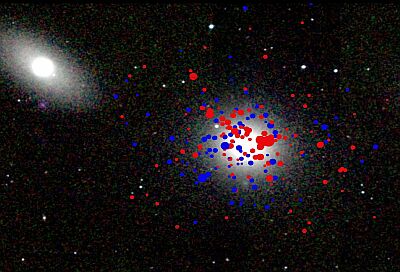

| TiO band at 7069.2 Å, observed

during the outburst of ρ Cas on 2000 July 19 in the top panel,

best fitted (dotted line) for a model atmosphere with Teff = 3750

K and log g = 0 in the bottom panel. The spectrum of 2002 January with higher

Teff does not show the TiO bands. A microturbulence velocity

of 11 km s-1 and macrobroadening of 21 km s-1 are

required to broaden the synthetic spectrum (dotted line) of ρ

Cas to the observed shape of the TiO band. The best fit yields a radial velocity

of -82 km s-1, or an expansion velocity of 35 km s-1.

The strongest TiO lines for the synthesis, with log gf values greater than

-1, are marked (vertical lines). The synthetic spectrum for Betelgeuse (lower

dotted line) and the fit parameters are also shown. [ GIF ] |

ρ Cas experienced periods of excessive mass loss in 1893 and around 1945, that appeared to be associated with a decrease in effective temperature and the formation of a dense envelope. The results suggest that ρ Cas goes through these events every 50 years approximately.

The recurrent eruptions of ρ Cas recorded over the past century are the hallmark of the exceptional atmospheric physics manifested by the yellow hypergiants. These cool luminous stars are thought to be post-red supergiants, rapidly evolving toward the blue supergiant phase. They are rare enigmatic objects, and continuous high-resolution spectroscopic investigations are limited to a small sample of bright stars (only seven of them are known in our Galaxy), often showing dissimilar spectra, but with very peculiar spectral properties.

Yellow hypergiants are the candidates "par excellence" among the cool luminous stars to investigate the physical causes for the luminosity limit of evolved stars. They are peculiar stars because they display an uncommon combination of brightness and temperature, which places them in a so-called Yellow Evolutionary Void. When approaching the Void these stars may show signs of peculiar instability. Theoretically, they cannot cross the Void unless they have lost sufficient mass. During this process these stars end up in a supernova explosion: their ultimate and violent fate. The process of approaching the Void however, has not yet been studied observationally in sufficient detail as these events are very rare.

Since the event in the year 2000, ρ Cas' atmosphere has been pulsating in a strange manner. Its outer layer now seems to be collapsing again, an event that looks similar to one that preceded the last outburst. The researchers think ρ Cas, at a distance of 10,000 light-years away from the Earth, could end up in a supernova explosion at any time as it has almost consumed the nuclear fuel at its core. It is perhaps the best candidate for a supernova in our Galaxy and the monitoring of this and other unstable evolved stars may help astronomers to shed some light on the very complicated evolutionary episodes that precede supernova explosions.

|

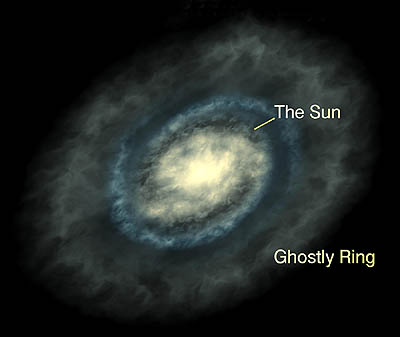

| Movie of ρ Cas recent evolution.

Artist's impression. Credit: Gabriel Pérez Díaz and the Instituto

de Astrofísica de Canarias. [ MPEG | AVI ] |

Some references:

- Cooper, K., "When

Stars get hyper!", Astronomy Now, Vol. 17 No. 6, 74.

- Lobel,

A., et al., 2003, "High-Resolution Spectroscopy of the Yellow Hypergiant

ρ Cassiopeiae from 1993 through the Outburst of 20002001", ApJ, 583, 923.

- "The William Herschel Telescope Finds the Best Candidate for a Supernova Explosion", ING Press Release, 31 January 2003.

- "Ro Cassiopeiae: La estrella que anunció la entrada en el nuevo milenio con una espectacular explosión", IAC Press Release, 8 January 2003.

- "La explosión de ro de Casiopea", IAC Noticias 1-2003, 23.

- "Telescoop

vindt op ontploffen staande ster", NWO Press Release, 31 January 2003.

- Alex Lobel's web pages on ρ Cas.